One of the enduring questions about Gratian’s Decretum is the relative darth of surviving manuscripts of what must have been one of the most popular and necessary law books of the medieval period. Because Gratian’s Decretum was the basic canon law textbook until 1917, it would seem that unlike many books that became dated either by shifts in theology or liturgy, the Decretum still had value as a working text in Catholic territories until the twentieth century. So what happened to all the copies of the Decretum? Were they read to death? Or have we overestimated its importance?

This project seeks to account for as many of the destroyed copies of Gratian’s Decretum as possible by looking at the plentiful scraps of the Decretum that were recycled into binding material. By gathering as much of this scrap material togehter as possible we hope to account for a percentage of the missing copies. We hope to provide specific evidence of where and when copies of the Decretum were turned into scrap. We also hope to answer broader questions about the destruction of medieval books in the early modern and modern periods: was the Decretum more or less likely to be turned into scrap than say, Peter Lombard’s Sentences, another book with long-standing importance in the Catholic tradition.

In addition to surviving manuscript waste, we hope to track references to the Decretum in book lists and inventories to get a sense of how many copies could be located at a given time in a specific place. By looking at surviving copies we may be able to determine how many can be accounted for, giving a very rough estimate of the chances of survival. Places to look: post-mortem inventories, catalogs, booklists, inventories of cathedrals, monestaries, priories, universities, etc, university chests and other evidence of books used as collateral for loans, and ownership notes in surving copies.

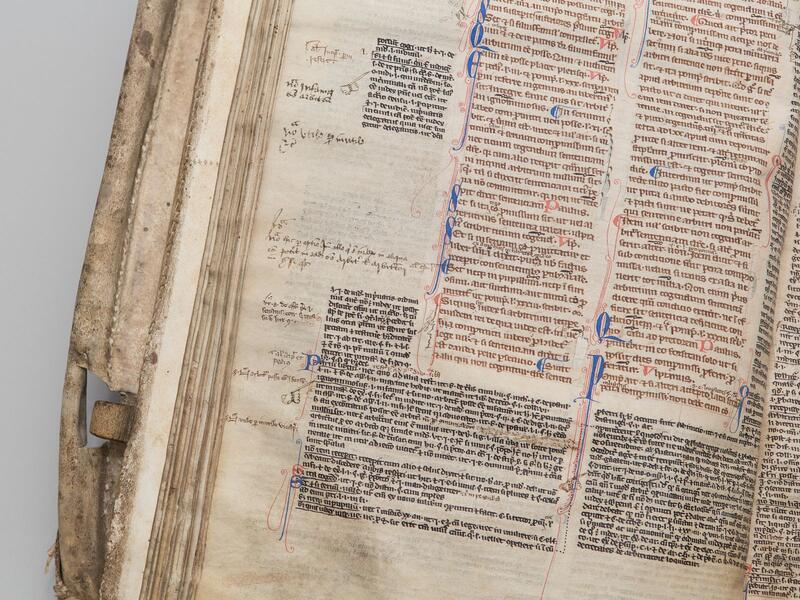

With a book as central to the education and practice of law, we can assume many reasons that copies of the Decretum may not have survived. One, of course, is overuse. As Winroth notes, oftentimes students would bring the cathedral’s copy of the Decretum with them when they traveled to study, and hopefully brought the book back when they were finished. The use of books by students, and especially their transport, must have led to the destruction of many Decreta. This is a well-used copy of Justinian’s Digest in the Beinecke Library that contains may layers of commentary on both the text and the gloss:

One possibility that might date the text is the presense or absense of commentary, and so our project will track whether our fragments have a gloss and if so, whose gloss.

Once the Decretum was printed (first by Heinrich Eggestein in Strassburg in 1471) we will begin to see fewer manuscript copies being produced, although simply because a printed book exists does not mean that people stopped using manuscript copies. Certainly the Reformation, which led to the rejection of Canon Law in Reformed territories, will account for the destruction of many Decreta. As important as the Reformation is the role of the Correctores Romani, whose editio Romana, published in 1582 “corrected” Gratian’s source material, making both earlier manuscript and print editions in some sense outdated. While many of these may have been recylcled, many were also burned in an effort to purify rather than simply break from the past.

As a crowd-sourced project, we seek your help in identifying fragments of Gratian’s Decretum, wherever they may currently exist. By comparing these fragments, we hope to identify which ones have been taken from the same codex so that we can begin linking those together in Fragmentarium. This will help us to visualize what the original codices must have looked like and hopefully provide information about the production, provenance, and ultimate destruction of the manuscript.

One doesn’t need to have professional photographs, although those are certainly welcome. In addition to photographs, the following bibliographic information will help us to identify codices and explore their history. Because many of the fragments are only a few lines, the line height and letter height will be very important for identifying fragments from the same codex. All measurements should be submitted in mm.

- Current Location (Country/City/Institution/Fount/Shelfmark)

- If still attached to its host: Author/Title/City/Printer/Date

- If still attached to its host: Early Provenance: Owner/City/Date/Price

- Range of text (Start/End)

- Gloss (present/author(s))

- Line height (text); Line height (gloss)

- Letter height (text); letter height (gloss)

- Number of lines (if full sheet): (text/gloss)

- Illuminated?

- Recension (we know one fragment of the first recension exists (Paris, B.N. lat. 3884, f. 1)

To participate in the project, please contact Raymond Clemens or Anders Winroth.

*The title of our project is taken from Anders Winroth’s The Making of Gratian’s Decretum (Cambridge, 2000).